Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom. Viktor E. Frankl

Mindfulness, at essence, means being focused on the present. Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), defines it as: “awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgementally”

There has, in recent years, been a surge of interest in the practice of mindfulness as being therapeutic for mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, as well a valuable contributor to general wellbeing.

This post considers the origins of mindfulness, its potential benefits, and how it may be incorporated into busy modern life.

Default Mode

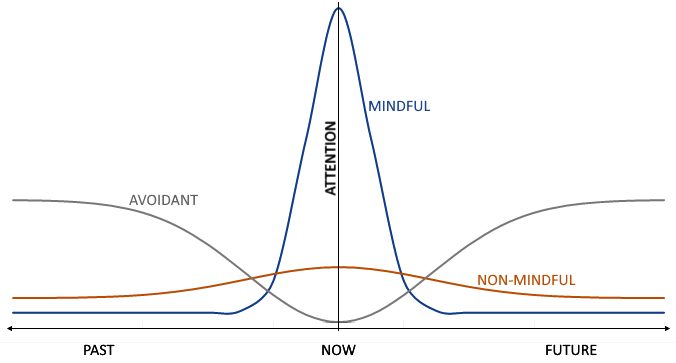

In its natural state the human mind typically spends much of its waking time flitting from thought to thought like a hyperactive butterfly, mostly re-visiting the past and/or in various imagined futures. This phenomena, known as the default mode, most likely evolved in order to consolidate the lessons of experience (ie if behavior x worked, repeat x; otherwise avoid x) and to prepare (rehearse) for potential upcoming challenges.

Given you’re reading this, you already have a 4-billion year unbroken lineage from the origin of life on earth, so the default mode has been so far apparently successful. However, evolved characteristics aren’t necessarily best suited to the relatively recent and ever more rapidly changing world modern civilised society.

Default mode can give rise to depression, eg by keeping the mind constantly focused on an inevitably imperfect personal past and all the associated feelings of regret, loss, guilt etc. Excessive fixation in the future may give rise to worries and anxiety as the mind anticipates all kinds of possible disasters, most of which will never happen.

Alternatively, default mode may encourage and facilitate avoidance of the actual reality that is here and now, eg: everything will be fine when I change job, move house, find my perfect soul mate, retire, win the lottery….. So we mitigate present discomfort by living in mental unreality. Maybe we can get through life on the back of never to be fulfilled fantasy, but it isn’t living optimally, and the background unease remains.

Origins of Mindfulness

Mindfulness has a long history dating back some 2500 years to the teachings of Hinduism (Andres Fossas, 2015). However, the most widely known tradition that embraces mindfulness is Buddhism.

Living around 500 BCE the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama), in the Four Noble Truths identified the fundamental cause of human dissatisfaction (dukkha) as being our constant, and ultimately doomed, attachment to what we have, and our perpetual and insatiable craving for what we want but don’t have.

For example, you’re enjoying a pleasant day with loved ones, but tomorrow your companions have to leave, you go back to your mundane job, and the weather forecast is not good. Can you mindfully enjoy the moment of now? Or do you already dread it ending and the (imagined) less pleasant tomorrow?

The Buddha proposed a means of escape from this otherwise eternal cycle of unsatisfactoriness, The Noble Eightfold Path, of which number 7 is Right Mindfulness.

Evidence

There is significant and growing evidence for the effectiveness of mindfulness; eg Gotnik et al. (2015) found “The evidence supports the use of MBSR and MBCT [Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy] to alleviate symptoms, both mental and physical, in the adjunct treatment of cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, depression, anxiety disorders and in prevention in healthy adults and children.” based on “a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews of RCTs, using the standardized MBSR or MBCT programs.” comprising 8,683 unique individuals with various conditions.

Other evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness includes Shapero et al. (2018), the Harvard Gazette (2018), and the Mental Health Foundation.

Mindfulness Practice

Many people experience mindfulness naturally, eg when you’re engaged in something really interesting and/or requiring intense focus such as a hobby or painstaking but satisfying task, it’s most likely you’re doing that mindfully.

The intentional practice of mindfulness, whether by meditation or focused awareness, helps periodically quieten the mind’s default mode, giving space to simply ‘be’. In so doing it promotes a more considered, objective and ‘mindful’ approach to life. Indeed, the specific practices described here should be seen as steps towards and components of the goal of mindful living, ie to shift the focus of attention from the non-mindful or avoidant to the mindful.

Mindfulness doesn’t deny past or future, rather it keeps these views in proper perspective, the past as a source of learning, and the future as the guiding light for present strategy.

Mindfulness Meditation

This is time set aside solely for the purpose of practicing mindfulness. Find a quite place where you won’t be disturbed and take a few moments to gather your thoughts and remind yourself of the purpose of the session.

The length of time allowed for meditation varies from person to person, typically starting with 5-10 minutes a day. If you really get into the practice and your schedule permits you may spend up to an hour in meditation, but shorter but regular sessions can also be beneficial. It’s better to actually do 5 minutes meditation every day than an hour occasionally when you remember / have the opportunity / feel inclined.

There are numerous guided meditations available on the Internet, eg those from UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center and UC San Diego Center for Mindfulness

Vary the meditation used to avoid complacency.

After a while you may find yourself sufficiently mindful that you can meditate without the audio. Typical components of a mindfulness meditation include initial settling down, scanning your body, focus on your breath and/or attentively listening to the sounds of your environment. Off-topic thoughts and feelings will inevitably come to mind. Simply notice them and return your focus to the target of attention. Do all this in a non-judgmental manner. Observe what is; do not seek to judge or change it.

Mindful Awareness

Most times our attention is anywhere but the present. Mindful awareness is the intentional act of directing focus to the here and now periodically throughout the day. It can be appropriate to practice during ‘down’ times such as waiting in line, travelling from A to B, or taking a coffee break, or useful during times of particular stress/anxiety (if you’ve sufficient presence of mind to do it – which is why it’s good to develop the habit under more normal circumstances).

Direct your mind to focus in detail on what’s happening around or within you at this moment. What can you see and hear? You might want to give an inner commentary; eg:

“there’s a black car, looks like a sports car, but it’s an older model, there’s a reflection of the building behind on its roof, some really ugly office block, all the windows look the same, but the one on the 4th floor has some plants, what kind of person might sit there…..”

Or you might focus within, again giving that inner commentary, eg:

“feeling a bit tired today, and a bit tense around the neck and shoulders, those new shoes are still a bit tight, it’s warm today, I didn’t need that extra sweater…..”

Doing this even for 5 minutes at a time, perhaps 2-3 times day develops the habit and breaks the dominance of the default mode. If you can bring yourself to do it during times of acute stress you’ll find the distress loses intensity and you’re then better able to make a reasoned choice of appropriate response.

Routine

Maybe because we find our daily schedule so tedious we tend to anesthetize ourselves wherever possible by switching to ‘auto-pilot’. The brain’s default mode loves routine, because by not having to focus on the present it gets free rein. But routine is the antithesis of mindfulness.

Promote mindfulness by disrupting routine. Inject variety into everyday life. It can be as simple as switching between drinking tea or coffee, taking different routes to work, changing where you eat lunch etc. Expand your reading matter, the type of TV show you watch, the vacations you take…

Try introducing an element of randomness to increase attentiveness; eg use the seconds counter on your watch or phone as a virtual coin toss – take a glance and if it’s odd, take the bus – or if even, walk.

Technology

Technology is a fine servant but a terrible master.

One of the most poignant scenes of the 21st century is the group of friends, physically together, but psychologically separate, each engaged via their phones in their own particular virtual world.

Technology is great; it’s doing more than probably anything else to re-unite humanity in its common oneness. Through technology we have access to practically the entire knowledge base we have developed throughout our history.

But, used inappropriately (to excess), technology becomes a curse, an addiction, a constant and never satisfied itch to check the latest Twitter feed / Facebook update etc. Work life too easily encroaches upon personal (real) life like a cancer eating away at what’s really valuable.

The mindful solution is to set limits. If you’re paid to work 9 to 5, work 9 to 5, and then stop! Sure, enjoy the Web, social media etc. But set limits, eg now’s my Facebook 1/2 hour or whatever, and stick to it. And if you can’t resist checking the latest updates rather than what you’re supposed to be doing, consider installing some kind of web blocking software.

What is “I”?

The practice of mindfulness gives rise to a curious paradox. Mindfulness involves the frequent non-judgmental awareness and observation of the body and mind; indeed it involves the patient and repeated training of the mind to be less in default mode and more in the here and now. But this raises the question of what is doing the observing (ie what is conscious)? And what is exercising the choice and agency that brings the mind back from its meandering to the present?

Is consciousness simply a side effect of the enormous complexity of the evolved brain? Is the presence of free-will, the ability of something (I?) to intentionally intervene in and tweak the natural laws to which the brain is subject, merely a persistent illusion?

Or is there some distinct, potentially non-material, “I” that has both consciousness and agency?

These are unanswerable questions, although the practice of mindfulness (like life) implicitly assumes the reality of “I”.

In Conclusion

While mindfulness is not a panacea for all the challenges of being human, it is a practice that can benefit many people. The human brain evolved in, and to cope with, very different conditions from the ever-demanding, ever-changing world of modern civilization.

Becoming more mindful helps tune out noise and better distinguish, interpret and respond to the signal of what’s really important, reality as it really is, and in so doing to live a more reasoned, meaningful and satisfying life.

Learn More

Books

Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life by Jon Kabat-Zinn

Mindfulness: A practical guide to finding peace in a frantic world by Mark Williams and Danny Penman

The Power of Now, Eckhart Tolle; this best-selling spiritual guide presents a strong version of mindfulness.

Why Buddhism is True by Robert Wright; describes how key teachings of Buddhism, including mindfulness, are supported by evolution and modern psychology.

Web

Mindfulness, NHS Moodzone; UK National Health Service guide to mindfulness to improve your mental wellbeing

How to look after your mental health using mindfulness, Mental Health Foundation

Can Mindfulness Really Help Reduce Anxiety? Shelley Kind, B.A. Stefan G. Hofmann, Ph.D. Boston University

How Mindfulness May Change the Brain in Depressed Patients, Alvin Powell

Guided Meditations

UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center

UC San Diego Center for Mindfulness

Guided Meditations – Tara Brach

MOOCs

Mindfulness for Wellbeing and Peak Performance and Maintaining a Mindful Life from Monash University

De-Mystifying Mindfulness from Universiteit Leiden

Buddhism and Modern Psychology from Princeton University

References

Andres Fossas. The Basics of Mindfulness: Where Did it Come From? Welldoing.org https://welldoing.org/article/basics-of-mindfulness-come-from

Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, Benson H, Fricchione GL, Hunink MG. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124344. Published 2015 Apr 16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124344 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4400080/

Mental Health Foundation. Evidence and research on mindfulness. https://bemindful.co.uk/evidence-research/

Alvin Powell. Researchers study how it seems to change the brain in depressed patients. Harvard Gazette. April 9, 2018. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2018/04/harvard-researchers-study-how-mindfulness-may-change-the-brain-in-depressed-patients/

Shapero BG, Greenberg J, Pedrelli P, de Jong M, Desbordes G. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Psychiatry. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2018;16(1):32-39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5870875/